December 31st, 2017

For the past several years for EAPs, the steady drumbeat of corporate wellness stories has sounded a uniform theme: corporate wellness/employee assistance programs do not yield a quantifiable return on investment. Yet, employer spending on wellness and EAPs continues to increase: $693 was spent per employee on wellness-based incentives in 2015, up from $594 in 2014, according to Fidelity and the National Business Group on Health.

This seeming disconnect is largely due to a misleading — or, in the case of some vendors, self-serving — means of evaluation. Measuring the success of employee assistance in particular has historically focused on utilization rates, client satisfaction, and occasional surveys of symptom reduction or problem resolution. The most reliable measure, however, is how EAPs affect specific workplace outcomes (absenteeism, presenteeism, turnover, workplace accidents, etc.).

Like everyday consumers, benefits and HR purchasers will choose their particular version of value when selecting employee benefits, which is always a balance between costs and perceived or expected results. In the context of employee benefits, value can be defined as “outcomes achieved relative to cost incurred.” If you accept this definition, then demonstrating value requires the measurement and regular monitoring of outcomes.

Benefit purchasers have not typically viewed outcome measures among their various benefit offerings and vendors as being very persuasive or credible, which leaves the lowest price as the one measure they do understand. Not many really support paying for an employer-sponsored benefit or service that does not produce positive results, but in the absence of routine outcome monitoring, there is usually no link between price and expected results. Consequently, employee benefit vendors and plans are currently not paid in proportion to their actual effectiveness, which is unlikely to change unless purchasers embrace and require their vendors to demonstrate a capacity to measure outcomes. Employee Assistance and Work-Life Programs, or EAPs, are a quintessential example of this phenomena — an employee benefit historically focused on utilization, program features, and of course the lowest possible price.

Despite being the first entry point for more than 150 million American workers seeking professional support, short-term counseling, and referrals for any personal or behavioral health concern, many EAPs continue to operate without knowing or improving their outcomes — until recently. There is increasing recognition among EAP providers that in order to continue to thrive, the EAP field needs to be able to measure and demonstrate effectiveness in quantifiable business terms.

Benchmarking EAP

The Employee Assistance Professionals Association — the professional association for EAP providers — endorsed a specific tool as an EAP best practice for measuring and evaluating work-related outcomes of services provided by EAPs. In voicing its support, EAPA believes that it can collectively advance the field by encouraging EAP providers and professionals to use the same tool for measuring workplace outcomes. This tool — known as the Workplace Outcome Suite (WOS) — is a scale developed by the Chestnut Global Partners (CGP) Division of Commercial Science.

The WOS is currently the only publicly available, free instrument that has been psychometrically validated and tested for use in EAP settings. Encouraging EAP providers to use the same outcome tool and share data is the only way the field will ever be able to truly compare and study outcomes across program models, industries, geographies, referral types and other variables.

The WOS uses a short, precise, and easy-to-administer survey that collects EAP-specific outcome data on both before (pre) and after (post) EAP service use among employees who utilize their EAP service. The WOS is a measure of change that examines five key aspects of workplace functioning: absenteeism, presenteeism, work engagement, life satisfaction and workplace distress.

1) Absenteeism (looks at the number of hours absent due to a personal problem taking the employee away from work). “Includes both complete eight-hour days and partial days when the employee came in late or left early.”

2) Presenteeism (measures decreases in productivity even though the employee is not absent per se but not working at his or her optimum due to unresolved personal problems). “My personal problems kept me from concentrating on my work.”

3) Work Engagement (refers to the extent to which the employee is invested in or passionate about his or her job). “I am often eager to get to the work site to start the day.”

4) Life Satisfaction (addresses one’s general sense of well-being). “So far, my life seems to be going very well.”

5) Workplace Distress (examines the degree of anxiety or stress at work). “I dread going in to work.”

Results of study

The most recently available pooled data-base shows a total of 13,400 EAP users from more than 50 different EAP providers (both internal and external) have been assessed both before and after EAP use with the Workplace Outcome Suite. This is a very large and persuasive sample size.

The WOS pre-test was administered to employees by trained intake workers before any intervention occurred. A key aspect of the WOS is to determine if an improvement in work performance occurs after the use of EAP, and so the post-test measure was not assessed immediately after the last EAP session.

Instead, the post-test was typically sent out about 90 days after the pre-test as an email link, or the employee was contacted by phone to complete the post-test. This simplistic design, known as “correlational” or “before/after” can identify if employees are improving at work, but it cannot definitively explain why. Its purpose is to test association, or how EAP intervention and workplace outcomes relate to each other in nature and strength.

The data were analyzed by examining changes in average WOS scores before employees received EAP services and then after services were rendered. The formula for calculating a percent change is “Post minus Pre divided by Pre.” For example, a post of 2.51 – a pre of 3.36 = -.253 or an improvement of 25.3%. The term “statistical significance” indicates there is a very high probability that an actual change occurred.

The results are good news for the EAP field. All changes were statistically significant, and the percentage difference in pre/post EAP scores is substantial (with the exception of work engagement at 7%).

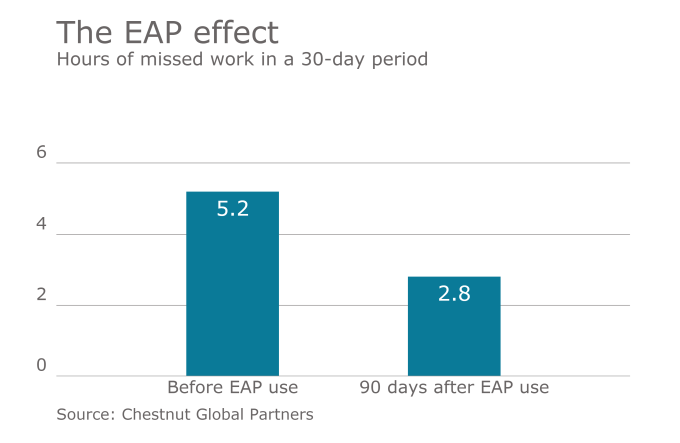

· Change in work absenteeism: Before EAP services, participants missed 5.2 hours of work over a 30-day period. Ninety days after EAP services, participants only missed 2.8 hours of work — an improvement of 46.4%.

· Change in work presenteeism: Before EAP services, 3.3. Ninety days after EAP services, 2.4 — an improvement of 26.7%.

· Change in work engagement: Before EAP services, 3.2. Ninety days after EAP services, 3.4 — an improvement of 7.1%.

· Change in work distress: Before EAP services, 2.2. Ninety days after EAP services, 1.9 — an improvement of 12.8%.

· Change in life satisfaction: Before EAP services, 3.0. Ninety days after EAP services, 3.6 – an improvement of 21.9%.

The usual methods of determining EAP effectiveness have included citing end user utilization rates, client referrals, satisfaction scales with poor return rates and even website click-throughs.

The workplace outcome approach represents a departure from conventional measures by objectively identifying when EAP services demonstrably work in the context of the workplace. Absenteeism and presenteeism effects are particularly strong, likely producing cost savings through productivity enhancements that may exceed the expense of the EAP itself.

Also see: “Top 10 EBA stories of 2016.”

Even without knowing the types and severities of presenting concerns, EAPs help employees to substantially increase their degree of satisfaction with life.

Although EAP use does move work engagement in a positive direction, the effect is much smaller. It may be that effective EA intervention reduces stress or anxiety in a manner that inhibits work engagement — or perhaps the EAP counselor cannot directly impact workplace conditions that foster higher levels of work engagement. Finally, use of EAP does seem to reduce feelings of distress or anxiousness about being at work.

It is worth mentioning there is a high degree of variability or difference among the many EA providers who submitted data and thus, the EA intervention itself is not well defined, but rather generic. However, this outcome data suggests that “generic” EAP intervention seems to be having a substantial workplace impact. We would be more effective as a field if our collective efforts at intervention were more highly specified and described. This way the most successful interventions that contribute to the greatest outcomes could be more easily replicated.

With more than 500 EAP firms using the WOS and 13,400 individual users in the EAPA/WOS database, these pooled results to date demonstrate that EAP intervention can be highly effective at improving these five workplace variables.

Tags: EAP, employee assistance program

Comments are closed.